[3.9.1] Quibusdam haec placet causa: Although Seneca stated that the search for “causes” was one of the objectives of the work (cf. 3.pr.1), this is the first use of causa since (see Bobzien 1999 for more on Stoic causation, and Limburg 2007: 176-82 for more on causation in NQ 3). It will appear frequently from this point forward. This section in large part follows what Aristotle wrote about rain and water vapor in his Meteorologica 346b16-347a13, but with the additional information about what happens to air underground. The table below shows how the elements relate to one another.

aiunt habere terram intra se recessus cavos: This theory is important for Seneca and he repeats this language at 3.16.4 and 6.13.3. It ultimately seems to derive from Aristotle (Mete. 349b3-30; cf. Gilbert 1907: 432-3, Bravo Díaz 2013: 150n.23). Anaxagoras thought that there was a vast cavern full of moving water in the earth (Hippol. refut. 1.8.5).

multum spiritus: For air under the earth, cf. Arist. Mete. 366b14-22. For Aristotle and Seneca this air causes earthquakes (cf. NQ 6.21.1) and Seneca’s use of spiritus gives such air “a specially vital and vitalizing force” (Williams 2012: 247). Seneca frequently elides the difference between spiritus as Stoic pneuma and air, which can lead to questions of how “Stoic” his conception of the natural world really is, see Graver 2000: 53-54.

necessario frigescit umbra gravi pressus: The transmutation of elements into one another will be stressed subsequently, cf. note on NQ 3.10.1. Here the air is cooled by underground darkness “necessarily” (cf. 3.25.10 for another example of such a “necessary” transformation and elsewhere in the NQ at 4b.13.5, 6.13.3, 6.21.2, and 2.15.1). The use of necessario stresses how normal and de rigueur such manifestations are and, therefore, they should not astonish or trouble the reader. umbra gravi is a poetic phrase found emphatically in Verg. E. 10.75-6, but deriving from Lucr. 6.783. Seneca alludes to Vergil’s “heavy shade” at Oed. 542-3: medio stat ingens arbor atque umbra gravi / silvas minores urguet in developing a locus horridus in response to the traditional locus amoeneus of pastoral.

piger et inmotus: When air becomes “slow and unmoving” it can turn to water (cf. Stobaeus 1.129.4). Seneca often uses piger of standing or slow waters, e.g. Med. 764, Phaed. 14, Thy. 665. This language is redolent of descriptions of the underworld in Senecan tragedy, cf. Herc. F. 704-5: immotus aer haeret et pigro sedet / nox atra mundo. There is something spooky or uncanny about Seneca’s description of this underground world.

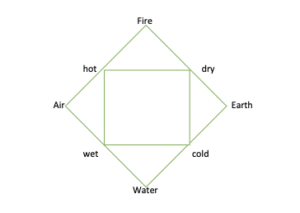

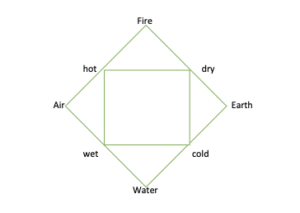

in aquam…convertitur: convertere is important for this section on transformation and appears often in the upcoming passages (3.9.3, 3.13.1, 3.15.6). From a literary perspective, Ovid's Metamorphoses is often in the background as Seneca demystifies such transformations. From a philosophical perspective, Empedocles first argued for the four elements (Graham 2010: 344-51 for primary texts; Lucr. 1.714-17). Empedocles called these ῥιζώματα (Diogenes Laertius 8.76 quotes the pertinent lines), whereas Plato coined the term στοιχεῖον (Tim. 48b) for elements (based on the word for letters of the alphabet). Seneca engages in subtle wordplay to hint at this tradition of element/alphabet, see notes at 3.10.4 infra. Aristotle discusses how elements change in De Generatione at Corruptione (esp. 318b1-319b1) and he likewise believes that the condensation of exhalations under mountains was the source of rivers (Mete. 349b19-35). Stobaeus attributes elemental flux to Chrysippus (Anth. 1.10.16c = SVF 2.413), and Cicero reports this transformation at Nat. 2.84. These transformations can broadly be seen as condensation and rarefaction, as Galen reports (SVF 2.406), cf. Hahm 1977: 244-47 for the Stoic view of the cosmic cycle as condensation and rarefaction.

[3.9.2] cum se desiit ferre: The lack of movement (s.v. OLD 5) spurs the transformation of air to water. Seneca will describe how wind is a movement of air and how air is nearly always in motion (NQ 5.1.1-5).

quemadmodum supra nos: Seneca is setting up the analogy between the upper world and the lower world, which he will emphasize at NQ 3.16.4 (crede infra quiquid vides supra), as well as the way that every element is suitable for change. There are limitations to this, as Hine realizes: “Seneca, like most ancient scientific writers, takes for granted the theory of four elements – fire, air, water, earth. They can all change into each other, but there are no precise rules governing when and how they can do so, and no experiments to test hypotheses about how such changes occur. Nevertheless, Seneca and other ancient writers on meteorology were performing a service to later science in their restless exploration of the linguistic and logical possibilities of key terms like element, hot, cold, dense, and rarefied by laying conceptual groundwork for a time in the distant future when experiments could clarify such concepts and measure such properties” (2010: 7-8). It is notable that water is the element whose changes can be more readily observed. Seneca likes the phrase supra nos, using it nine times, including the following sentence.

aëris mutatio imbrem facit: It is possible that Seneca would have addressed this topic more extensively in the missing section of 4b. It appears elsewhere in the NQ at 4b.4.2 where Seneca quotes Vergil’s cum ruit imbriferum ver (G. 1.313) and comments vehementior mutatio est aeris undique patefacti et solventis se ipso tepore adiuvante…, and at 2.12.4. Aristotle writes that this could happen (Mete. 349b16), but for modern hydrologists, it is clear “Compared to the rainfall theory of the Presocratics, Aristotle’s explanation is definitely a step backward in the development of hydrologic theory” (Brutsaert 2005: 563).

infra terras flumen aut rivum: The air under the earth that becomes water in the form of rivers or streams. Seneca often pairs these terms in the NQ, cf. 3.6.2, 3.12.3 and 3.15.5.

segnis diu et gravis: variatio of piger et inmotus above, but with the additional association with the weight of the water vapor (that is, aëris mutatio) with the adjective gravis transferred from a figurative usage (umbra gravi) to a more concrete. Seneca will devote a section (3.25.5) to the heaviness of different waters.

sole tenuatur: NQ 1.2.4 discusses how nothing heavy is able to exist close to the sun.

ventis expanditur: The air is either rarified by the rays of the sun or scattered by the winds. Note how this verb is part of his definition of air and wind (NQ 5.6.1). This is the reason why rain showers are only intermittent (intervalla imbribus magna sunt), whereas the metamorphosis of air into water underground can happen continually, thus resulting in the large reservoirs of water in the earth.

intervalla imbribus magna sunt: The rhythm of imbribus magna is preferable to magna imbribus (which is found in some manuscripts). Cf. detractos terra at 3.8.1.

quidquid est quod illum in aquam convertat: Seneca does not deign to know what exactly causes the transformation, but the following catalogue of underground characteristics implies his belief that these alone or in tandem are the primary cause(s).

idem semper est: Seneca will reuse this language to contrast what is able to be born in the air (NQ 7.22.1: quomodo potest aliquid in aëre idem diu permanere, cum ipsa aër numqum idem diu maneat? fluit semper, et brevis illi quies est). If these conditions are always the same, they will lead to the same outcome, semper ergo.

umbra perpetua, frigus aeternum, inexercitata densitas: Lucretius used frigus aeternum to describe a corpse at 4.923-4 (namque iaceret / aeterno corpus perfusum frigore leti) and Seneca uses it to describe the waters of the locus horridus of the necromancy scene in his Oedipus (546). The air that remains underground will attain harmful qualities, according to NQ 6.28.2 (a passage that features similar language, e.g. aeternum illud umbrosi frigoris malum). densitas is uncommon in Seneca, only appearing in two other passages dealing with shade (densitate ramorum, Ep. 41.3) and the ability of the sun’s rays to burst through even the densest cloud (omnem densitatem perrumpere, NQ 1.8.2). Seneca will use inexercitata later to describe the insalubrious creatures born in the waters underground.

praebebit…causas: Livy is fond of praebeo+causa (e.g. 3.13.3, 27.34.8, 30.4.9), as is Ovid (e.g. Ars 3.40, Fast. 1.674, 3.549). Seneca applies it elsewhere at Ep. 99.3 and NQ 2.11.2.

[3.9.3] placet nobis terram esse mutabilem: nobis here indicates the Stoics, cf. SVF I.495 (a view of Cleanthes), II.413 (Chrysippus’ opinion). He will use this formulation also to describe additional Stoic ideas (NQ 3.22.1: aliud est aquarum genus quod nobis placet coepisse cum mundo; 6.21.1). This will be important later in this book during the flood (quia tunc maxime in umorem mutabilis terra sit, 3.26.1; maximam tamen causam ad se inundandam terra ipsa praestabit, quam diximus esse mutabilem et solvi in umorem, 3.29.4), cf. Berno 2012: 52-5 for more on these passages.

quicquid efflavit: Elsewhere in NQ Seneca will write that vents of air in the earth emit noxious gases (6.27.2), whirlwinds born from quicquid umidi aridique terra efflavit, 7.8.1; and Posidonius’ theory of terrestrial emissions (2.30.3, 2.54.1). Here, he is making the point that certain emissions occur within the earth and are changed into water when they are not exposed to the open air (libero aëre).

crassescit protinus: The inceptive crassescit makes it seem as if the transformation begins to happen immediately (protinus). crassescere is often used of condensation, cf. Pliny Nat. 2.114.

habes primam aquarum sub terra nascentium causam: The second-person address, much like at the conclusion of section 3.8, reaffirms the argument and acts to address what the reader has discovered in this paragraph in part by reiterating language from it (e.g. sub terra) and doubling down on the personification of water as something that can be “born” (as at 3.3.1: nasci).